This is the first part of a paper I wrote in 2018 for a class in American Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill. It tells the story of the founding and building of the Coker Arboretum at UNC-Chapel Hill.

INTRODUCTION AND CHAPTER ONE

Dead fancies these, yet, how I cannot tell,

My trinity of youth reborn again

Beget a rapture which is almost pain;

And, as I hear the University bell

Ring out the session of the noonday class,

It seems not now, but seven years ago,

Time an illusion, and mankind’s mute woe

A thing that cannot touch me, nor harass;

And I a student, fresh from poring on

Hellenic verse or Latin lexicon,

Come to renew my soul in autumn’s miracle.

from “The Arboretum, Chapel Hill” by Philip Macon Cheek, 1945 (Philip Macon Cheek was both an alumnus of UNC (Ph.D. 1931) and an instructor in English. This poem was collected by William C. Coker and appears in his papers held by Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

The Coker Arboretum at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill turned 115 years old in 2018. Before botanist and faculty member William Chambers Coker began work on the site in the early 20th century, it was a bog in a low-lying area just east of the main campus, good only for grazing livestock. Today, the manicured garden hosts over 500 species of native and non-native trees and shrubs, with neither a trace of its original swampy state nor the amount of labor dedicated to its building obvious to the visitor. Considering that the cornerstone for the oldest building on campus, Old East, was laid in 1793, and that the University was chartered even earlier in 1789, the Arboretum is a relative newcomer as far as canonical fixtures of the Chapel Hill landscape. Regardless, the space has become one of the University’s signatures and plays a role in the experiences of many students, staff, townspeople, and outside visitors. The Arboretum is patronized by individuals ranging from garden enthusiasts to students looking for a place to study, and its immediate function to them may obscure awareness of the Arboretum’s history. A consideration of the full history and context of the Arboretum project at UNC-Chapel Hill, however, reveals the importance of the site in understanding larger social issues and dynamics relating humans to space, memory, and time in the story of Chapel Hill.

Here I focus mainly on the founding and building of the Arboretum in the early 1900s, placing the development in context of historical foundations, trends, and events of the Progressive Era in the South. I establish meaning for why the site is used and inhabited in different ways, how the space has imprinted on the community, and how that has changed over time. I argue four main points. First, the Coker Arboretum is a manifestation of science and progress created in the New South, representing rebirth, freedom, and truth. Second, the Arboretum is a site of memory that also represents eternity and immortality; consequently change to the landscape is perceived as destruction and provokes tension. Third, the educator and scientist for whom the Arboretum is named, its builder William Chambers Coker, is a storied figure perceived as a Great Man, one in a long line of white men with great power and ties to the Confederacy who built UNC. Finally, the Coker Arboretum was a civilizing project, and as an expansion of the UNC campus, is a continuation of the endeavor to create white spaces; it is therefore a racialized landscape.

The Land and the Hill

Before engaging with the Coker Arboretum as a discrete space, it is necessary to first place the environment where it lies in context through discussion of how the land and terrain themselves have been romanticized and incorporated into the founding myths of the University of North Carolina. Most accounts begin shortly before William Richardson Davie and UNC’s other “founding fathers” visited what was known as New Hope Chapel Hill: UNC’s 19th century mythmaker-historian, community member, and enslaver Cornelia Phillips Spencer, daughter of a professor and sister to two scholars, explained,

“Chapel Hill was certainly a local habitation, and had a name, before the days of the Revolution, for the ruins of a Chapel of the Church of England were

plainly visible forty years ago…”

“Forty years ago” was 1826. Spencer quoted, page 2, in Chamberlain, Hope Summerell. Old Days in Chapel Hill: Being the Life and Letters of Cornelia Phillips Spencer. United States, University of North Carolina Press, 1926.

To the eye of the founders of the University at the close of the Revolution, the “ruins” of British colonial rule must have seemed very far removed — indeed ancient, relics of a corrupted era — considering the promise of their grand task ahead, a task that was both modern and quintessentially American.

Chapel Hill, true to its name, is built on an elevated portion of land. During the Triassic period, 200 million years ago, as Pangea broke apart, a rift basin formed in what is now called the Piedmont area of North Carolina, where Chapel Hill lies. Kemp Plummer Battle, historian/mythmaker, UNC faculty member, enslaver, and alumnus, goes into some elaboration about the ancient landscape in his History of the University of North Carolina: “The eminence is a promontory of granite, belonging to the Laurentian system, and extends into the sandstone formation to the east, which was once the bed of a long sheet of water stretching from near New York to the centre of Georgia” (1:25).

Before white settlers, Native Siouan communities lived in what is now Orange County. Renovation of the James Lee Love House on Franklin Street in Chapel Hill in 2004 revealed artifacts proving that Indigenous people lived where campus is now from 500 B.C. to 500 A.D. The Occaneechi have lived in the Piedmont region – modern day Orange County – well before the arrival of white settlers. The Occaneechi are descendants of the Saponi people and the tribe is based today in what is now Alamance County. Their habitation and relationship with the land where UNC now stands is barely considered in the canonical accounts of institutional history, as the area was seen as a blank slate upon which to build.

Historians of UNC, official and otherwise, are universally smitten with the “natural, inherent beauty” of Chapel Hill, and this comes into play in the early 20th century when the Arboretum becomes a beautification project in honor of the site of the University. This “magical landscape” notion factors heavily into UNC-centric nostalgia and contributes to the mystical nature of the entire project of building America’s first public university. Librarian and professor Louis Round Wilson explains the magic of William Davie’s eureka moment: “They fell under the spell (italics mine) of the beauty of hill and valley… For them only one decision was possible. There was no need to seek further. Here was a place in the center of North Carolina that could not be matched elsewhere for natural charm” (Wilson, Louis R., and Edward Weaver. The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University. University of North Carolina Press, 1957, page 373). After dining under the same poplar supposedly still standing on Carolina’s upper quad, lore states that William Davie realized that he should build a university on the spot, partially because of the quality of water: “There is nothing more remarkable in this extraordinary place than the abundance of springs of the purest and finest water, which burst forth from the side of the ridge, and which have been the subjects of admiration both to hunters and travelers…” (Battle 1:26). With so much construction today on top, it is not widely known that the main UNC campus is built over a system of creeks, a system given a mysterious and romantic name: “Meeting of the Waters.”

Others were also entranced by the water quality, but as record proves, even more so is there a near obsession with trees in Chapel Hill, which is also a factor as to why the Arboretum as a project would have such resonance. The original campus setting, now known as McCorkle place, was referred to by many as “The Grove” or “The Noble Grove,” in consideration of the wooded atmosphere. The founding myth revolves around a particular tree: the Davie Poplar, the one under which Revolutionary War hero William Davie himself had a grand vision to build America’s first public university. Of course, in Chapel Hill, only a tree could have wielded such power over a Great Man.

Recollections of Chapel Hill for those present around the turn of the 20th century, according to published accounts, almost invariably center trees. Although as woman she was not allowed to attend UNC, Cornelia Phillips Spencer nevertheless projects, “What student of all its hundreds has ever failed to cast a longing, lingering look back towards it, or has ever ceased to think lovingly of that time when he trod its walks, or reclined under the shade of its oaks.” (Spencer, Cornelia P. Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina, as It Has Been: Dedicated to the People of the State and to the Alumni of the University. Self-published, 1869, page 4.) Alumnus Thomas Wolfe wrote in Look Homeward, Angel, “The central campus sloped back and up over a broad area of rich turf, groved with magnificent ancient (italics mine) trees” (Wolfe, Thomas. Look Homeward, Angel. Simon and Schuster, 2006, page 323). In former Chancellor, professor, and alumnus Robert House’s recollections of his time as an undergraduate, he devotes a whole chapter to trees called, “Chapel Hill under the Trees.” He creates odes to them, over and over in his book: “My first impression of Chapel Hill was trees; my last impression is trees,” and, “It is no wonder that Chapel Hillians are ardent tree worshippers (italics mine) and that the symbol of the place is Davie Poplar” (House, Robert B., and Joyce Kachergis. The Light That Shines; Chapel Hill, 1912-1916. University of North Carolina Press, 1964, pages 8-9). Coker himself said of what makes UNC great and unique, “These are (1) its spaciousness, especially the open sweep of the large central rectangle, and (2) its noble and venerable trees (italics mine) that we must thank our fathers for seeking in the beginning and for preserving to this day. Nothing could so distinguish us as the presence of these trees, and in their possession we stand without a rival among the colleges of the country” (Coker, William C. “Our Campus.” University Magazine, Vol. 46, no. 4, 1916, p. 173-176.). How, then, could UNC not have an Arboretum?

Writers about UNC also tend to make explicit references to religious connotations of the landscape, weaving in connections between the setting and Greek and Roman symbols. “The situation is central, elevated, retired, and healthful. And how beautiful. Its hills and groves and glades are indeed fit to surround the walls of an Academe – beloved haunt of the Muses – sacred to all gentle and classic companionship” (Spencer 4). Battle quotes Reverend Samuel E. McCorkle, writer of UNC’s charter, at the laying of Old East’s cornerstone, “May this hill be for religion as the ancient hill of Zion; and for literature and the muses, may it surpass the ancient Parnassus!” (1:40). The fact of the university being placed on a hill has powerful symbolic resonance and impact, recalling “A City upon a Hill” parable and John Winthrop’s sermon “A Model of Christian Charity.” It is no accident, too, that The Well, probably the most important symbol and site at UNC-Chapel Hill, is neoclassical in design, once nicknamed the “little Grecian Temple.” Grand myths associated with the founding of America and related assertions of American Exceptionalism echo in UNC’s own story.

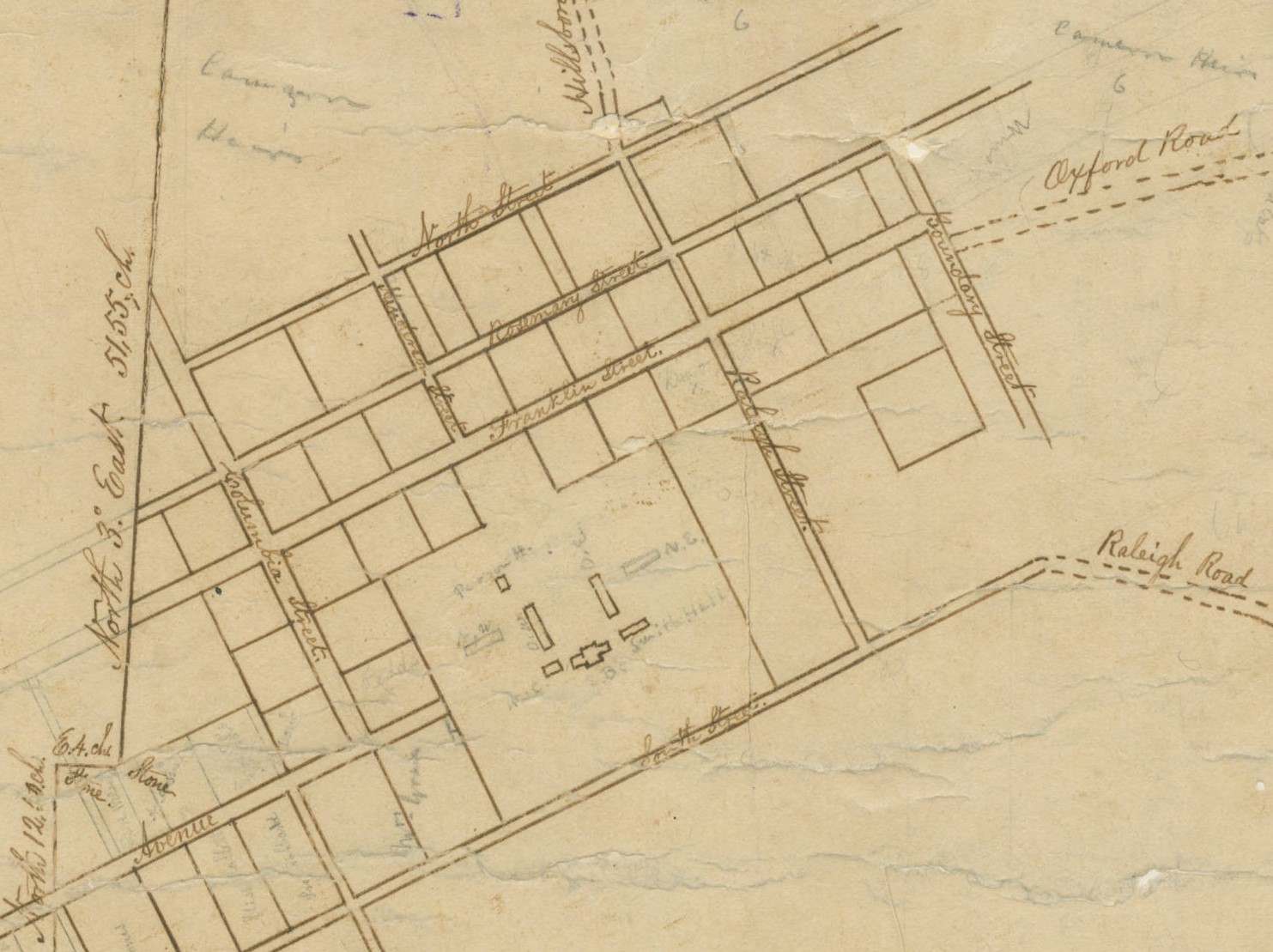

Despite accolades to the beauty, charm, and usefulness of the site for the university, the location where the Coker Arboretum now exists was initially unusable and could not be built upon. At the eastern edge of what is now McCorkle Place, alongside the thoroughfare to Raleigh, North Carolina called Raleigh Road (see Figure 1), the elevation drops fifteen feet (based on question and answer with Botanical Gardens staff, 2018), creating a low-lying area where water collected and the soil was poor. During the first century of the University of North Carolina, the area of about five acres was first fenced off with wooden stakes, and livestock was allowed to wander and graze there (Powell, William S., and Diane McKenzie. The First State University : A Pictorial History of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press, 1992, page 68; Battle 1:471).

Figure 1: Portion of map of Chapel Hill by Kemp Plummer Battle, 1852, showing the extent of campus at the time. In the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

As this paper will explain further, a few university leaders considered placing a garden there, even in the early days, but the conditions were so poor, its transformation confounded them (Henderson, Archibald. The Campus of the First State University. University of North Carolina Press, 1949, pages 268-269), and not until Dr. William Chambers Coker arrived at UNC in 1902 would someone grapple with the challenge of cultivating the space and see the project finally take form.